In October of 1775, the fledgling nation that would become the United States of America was in trouble. The British Navy—one of the strongest in the world—was using its military superiority to disrupt trade in the rebellious colonies and attack seaside settlements.

Something had to be done, or the American Revolution might fail almost as soon as it had begun. In response to the crisis, the Continental Congress formed a Marine Committee and charged its members to organize a navy. At the time, many colonists considered the project a fool’s errand. The colonies had no naval yards, no factories to produce artillery, and no hemp or sailcloth.

Nevertheless, on October 13, 1775, the Continental Congress voted to convert two sailing vessels into warships, arming them with carriage and swivel guns. And with this legislation, the nation’s navy was born. Over the next three years, the Continental Navy grew to include 50 armed ships of various types, some of them converted merchant vessels.

While the fleet was too small to take on the British navy’s full might, the Continental ships nevertheless played a key role in the Revolutionary War. They carried diplomats and correspondence to Europe, then returned with much-needed munitions. The American fleet also captured nearly 200 British vessels, dealing a serious blow to enemy morale and forcing the British to divert warships to guard key trade routes.

Small but mighty, the Continental Navy did its part to help the colonies win the Revolutionary War.

The New Steel Navy

After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. Navy was temporarily disbanded due to a lack of funds. For 12 years, beginning in 1785, the nation’s maritime duties were handled solely by the Revenue Marine, the forerunner of today’s Coast Guard.

But in the 1790s, the growing conflict with Algerian pirates made it clear that the United States needed a full-fledged navy to protect its trade routes abroad. To combat this threat and others, Congress passed the Naval Armament Act in 1794, authorizing the construction of six frigates. The U.S. Navy was back.

Over the next few years, the size of the Navy grew slowly. Nevertheless, this small fleet contributed greatly to America’s success in the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812. Even so, it would take a domestic conflict to push the Navy into an era of rapid change.

The Civil War brought great technological changes to the U.S. Navy. Steam power replaced sails. The wooden hulls of existing ships were reinforced with armor plating, while new ships were constructed entirely of iron or steel. Guns increased in both size and range, and gained the ability to turn in any direction, which meant that ships could achieve more firepower with less weaponry.

The Civil War also marked the first time that African-Americans served in the U.S. Navy in large numbers. During the war, 10,000 African-American men took on various duties, and seven of them earned the Medal of Honor.

One such man was Robert Blake, who proved his mettle while serving on the gunboat USS Marblehead. Blake had been assigned the non–combat role of steward. But when the Marblehead was hit by enemy fire, killing the man who loaded the rifle guns, Blake took over, running much–needed gunpowder to the guns, and enabling the Marblehead to return fire. His actions were later described as both “cool and brave” by the ship’s commander.

After the conclusion of the Civil War, the U.S. Navy entered another period of slow growth. But before long, it became clear to government leaders that if America were to take its place on the world stage, it would need a world-class navy. So in the 1880s, the U.S. began modernizing its naval forces. It launched the nation’s first steel warships—protected cruisers with names like Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago. Armored battleships soon followed. And then the US debuted a truly revolutionary technology: the submarine.

Under the Sea: The Birth of the Submarine

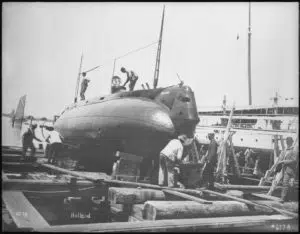

The world’s first combat submarine was invented and used briefly during the Revolutionary War. Called the Turtle, this craft met all the criteria of a submarine; it could submerge, maneuver underwater, and carry oxygen for its occupant. But the Turtle bore little resemblance to modern craft. It looked instead like a giant wooden beer barrel. It could carry only one person, and was hard to maneuver. Nevertheless, it proved that submersible technology was viable.

The U.S. Navy acquired its first official submarine in 1900. The USS Holland was nothing like the Turtle. Made of steel, able to accommodate a crew of six and dive 75 feet below the surface, the Holland looked much like today’s modern submarines, in shape if not in size. The Holland also introduced several key technologies: ballast and trim tanks to enable precise underwater maneuvers, torpedo tubes, and two pneumatic dynamite guns. The ship also had a gasoline engine for surface operations, and an electric motor for use when submerged.

The Holland was the first in an unbroken line of U.S. Navy submarines. The craft continued to get bigger and more sophisticated over the years, and the number of subs in the Navy fleet expanded. By the time World War I began, the Navy was able to deploy 72 submarines throughout the world.

But it wasn’t until the Second World War that submarines became a staple of naval operations. World War II was the first conflict in which submarine power played a decisive role, especially in the Pacific theater. Compared to their World War I ancestors, the submarines of the 1940s were bigger, stronger, and better equipped—both with more firepower and new technologies like sonar. During World War II, U.S. submarines destroyed more than 1,300 warships in the Pacific. Navy submarines also delivered troops for special missions, and rescued downed carrier pilots, including future President George H. W. Bush.

Help on the High Seas

Today, the U.S. Navy has more than 70 submarines in service within its fleet of nearly 450 ships. And while all the ships in the fleet are designed for defense, the U.S. Navy also has a long record of providing humanitarian aid, rescue services, and emergency medical assistance. Like all branches of the military, the Navy is often called upon to help in times of crisis, whether domestically or abroad.

Since the 1950s, Navy personnel have actively participated in disaster relief efforts throughout the world. They’ve mounted rescue operations after flooding in Kansas and Spain. They’ve brought in food and supplies after earthquakes in Alaska and Greece, and done the same after hurricanes in Texas and Haiti. They’ve also helped fight fires in California and Japan.

Navy personnel have rescued crews and helped damaged ships all over the world. In 1961, for example, the Navy rescued 84 seamen from two commercial ships stranded in the Pacific. And over the past few decades, the Navy has performed dozens of similar rescues, saving the lives of both seasoned crewmen and novice sightseers.

Dozens of countries and thousands of people have benefitted from the aid provided by the U.S. Navy.

PRIDE Welcomes Navy Veterans

Navy personnel’s training in service makes them sought-after employees once they return to civilian life. PRIDE Industries is fortunate to employ many Navy veterans and dozens of veterans from other branches of the military.

To seek out these highly valued employees, PRIDE developed the Military Skills Translator, an online tool designed specifically for veterans. With the Skills Translator, military veterans can easily determine which civilian jobs best correspond to the valuable experience they gained while serving our country.

To paraphrase Admiral George Anderson: Navy veterans have both a tradition and a future. PRIDE Industries is pleased to be part of that future for so many veterans.